Over the last two months our team has been talking with different technology firms and business leaders about what’s happening and what is next. The picture can vary depending on who you talk to and what they do, and we’ve found that there are some sources spreading information that ranges from helpful and informative to downright incorrect for employers to follow.

We have completed an overarching meta analysis of over 10 different studies and analyses representing tens of thousands of people around the globe. The key findings are below. The sources are listed at the end, for anyone that’s curious enough to explore.

The bottom line is that things are changing on a variety of levels, and making decisions based on outdated practices or information can lead to no results at best or poor results at worst. This is the time to re-evaluate the approaches that have always been and eliminate those “we’ve always done it this way” processes that do not contribute to positive outcomes.

More than anything, we’re doing this analysis as a way to prove that:

- There are credible, valuable data sources in the market that we can learn from and

- We need to be evidence-based where possible, using data to guide our decisions and approaches instead of just what feels right at the time.

If you would like a conversation with our research team to discuss what’s happening and how it intersects with the talent goals of your organization, please contact us here.

A Related Note about Change Strategy, Diversity, and Decision-Making

Research from Duke University shows that humans are bad at making decisions between two choices if there are many variables in play. It’s easy to choose between two types of ice cream because they are very similar. It’s harder to choose between ice cream and a slice of cake. The decision about when and how to change policies, return to the workplace, and adapt to the demands of a dynamic workplace are great examples of multivariate decisions: there are dozens of elements that must be considered, weighed, and judged before coming to a final decision.

One of the things we’ve worked with organizations on in the last two months is to think about what we’re calling Third Option choices. Essentially when you’re stuck between two choices and neither of them is a good one (leaving people at home forever versus bringing them back to the office immediately, for example), that’s a clear sign that we need more choices. More alternatives. More options. There is a time in organizational decision-making that we need to narrow our choices to a select few and make an ultimate decision, but that needs to come after we’ve created Third Option choices.

If you feel like you are weighing two equally bad options, stop and gather more ideas. For instance, many companies right now are struggling to support parents with children. The options seem to be letting them work from home indefinitely or requiring them to come to work. In a recent discussion with a group of CHROs, they explained that their firms were doing a range of things to support this need, from adopting flexible work schedules to company-sponsored daycare with small class sizes to job sharing and more.

One other aspect of decision-making that has come to the forefront in the last two months is taking into consideration the perspectives of your stakeholders. We know that we can make better decisions if we have a diverse group of people making them. We’ve all heard the “different perspectives” argument for having a diverse group of decision makers, which simply says having more diverse people in a group leads to more perspectives and thus more ideas.

However, the research shows that there’s a second layer to this. Simply having a diverse individual in a decision-making process leads others to naturally consider other viewpoints and create more potential solutions, even if the diverse individual never contributes a single idea. Obviously it’s better if they do, because they truly can bring a different layer of perspective to the decision, but even just creating more inclusive teams can lead to better and more helpful decisions. If you’re stuck creating Third Option ideas, this can help.

There’s never been a better time to make this change at a fundamental level, especially with so many different short- and long-term decisions that must be made that affect all of your workers and their varied and unique needs. Keep that in mind as you read through this analysis and think about how to put the ideas into action.

Flexibility is in High Demand, Both Now and in the Future

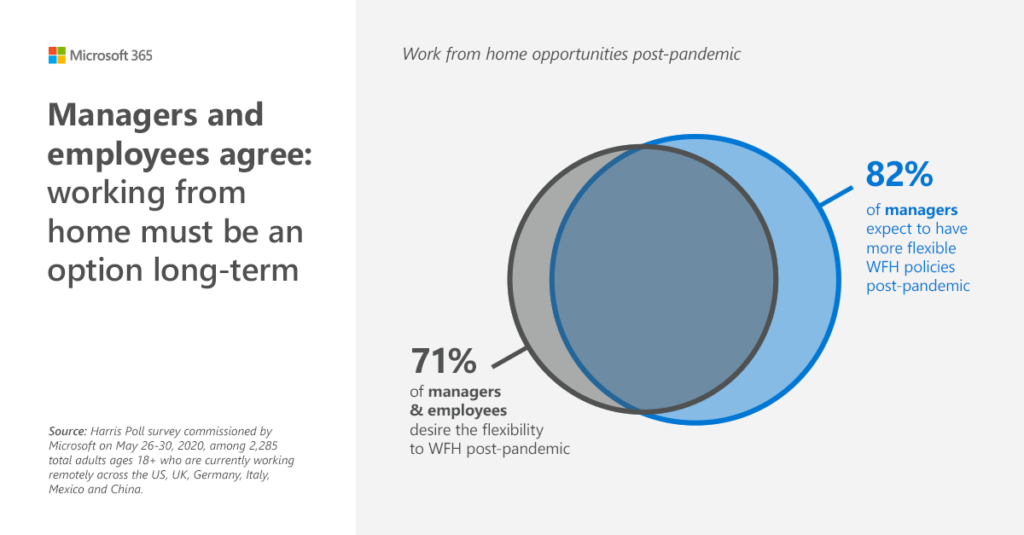

Data from Microsoft show that 71% of managers and workers want some flexibility for working from home going forward. Contrast that with a Xerox study indicating that 82% of the workforce will be back to the office within 12-18 months. That is going to be a challenging transition for those of us that work remotely or have had that experience, it’s easy to understand why:

- No commute: saves gas, stress, and time

- It’s easier to fit work to your life, not fitting your life around a work schedule that demands physical presence

- More time for family and other commitments, leading to greater satisfaction

The Mental Health Side of Forced Remote Work

Earlier this summer my team hosted an event featuring an organizational psychologist that provided insights on what she called “organizational trauma.” While remote work (as we’ll see in the next section) is an opportunity for many to create a series of new positive habits in a changing work environment, the truth is that other workers crave the in-person experience and have been affected negatively by isolation not just in a work context but in a personal context as well.

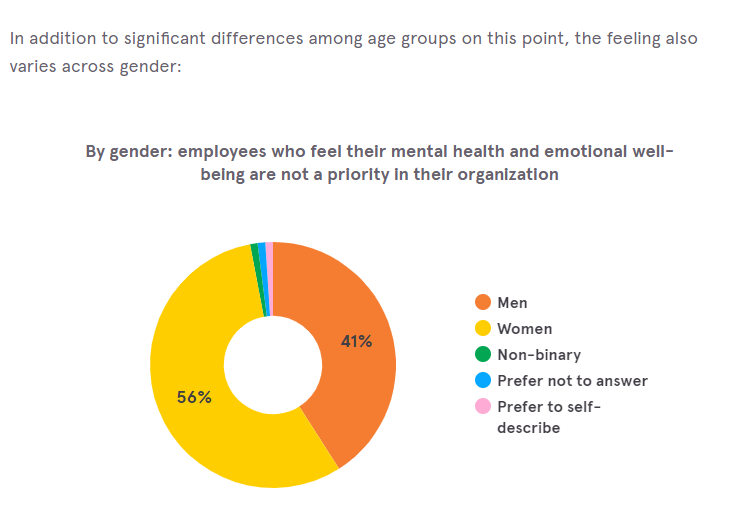

New data out from Headspace shows that about 30% of workers think they may have depression or anxiety because of the current environment. Women are more likely than men to believe this, as the graph below illustrates.

Getting Comfortable with Remote Work as a New Habit

Research from University College London shows that, on average, it takes about 66 days to create a new habit. In the first weeks of the pandemic lockdown, people and businesses responded as if the change was temporary. But the longer it has gone, the more solidified these new habits (including working from home) have become. For those employers who have publicly stated that workers can continue working from home for the foreseeable future (such as Google and Atlassian), making any change to that approach is going to lead to friction for those who have become enamored with the value and freedom associated with remote work.

A few years back when IBM decided to kill remote work and bring workers back to the office, a percentage of that group decided to leave instead of returning to a physical office because working virtually, for some of us, is more productive than reporting to a physical location.

In the COVID era, one of the first things that happened in the shift to working from home was adding hours to the workload. In a talk with a program manager this last week, he explained that his issue is that his team is spread across the country and when someone needs something at 7pm, he still feels like he has to get a response in that day instead of waiting for the following morning.

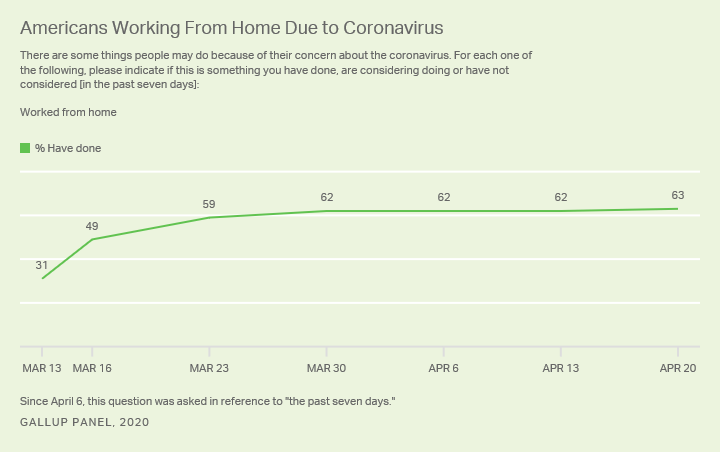

This is indicative of a larger overall trend. Initially, the shift for many workers was a challenge. FlexJobs, which keeps track of the percent of the workforce that is remote, estimated that just 3-4% of workers were working remotely in February 2020.

In May, Gallup data showed that this had jumped considerably to over 60%.

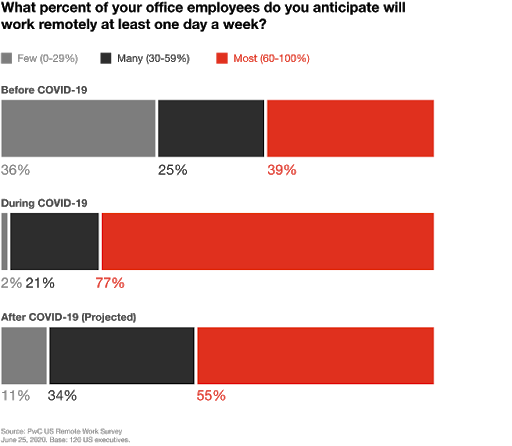

PwC data show a slightly different lens, but still relevant to the discussion:

Remember the statistic on 66 days to build a new habit? It’s interesting to watch the qualitative responses to surveys change during the COVID transition to remote work.

The workers that moved into a remote working arrangement began changing their tune in qualitative surveys after a “few months” of being remote (remember the 66-day average on forming new habits). These are some of the comments that began to appear after that timeframe about their attitudes toward work:

- “falling into a consistent routine”

- “forming a pattern [of work time and breaks] with my coworkers”

- “I think it’s weird how normal everything has become”

Humans are adaptable creatures. In a study by our team in 2019, we found that the number one skill that workers and employers think is critical is communication skills. It’s not coding, or data science, or any number of specific hard skills. Every job requires some measure of communication for success, and some depend more heavily on it than others.

In a world that is more remote, communication is more critical than ever.

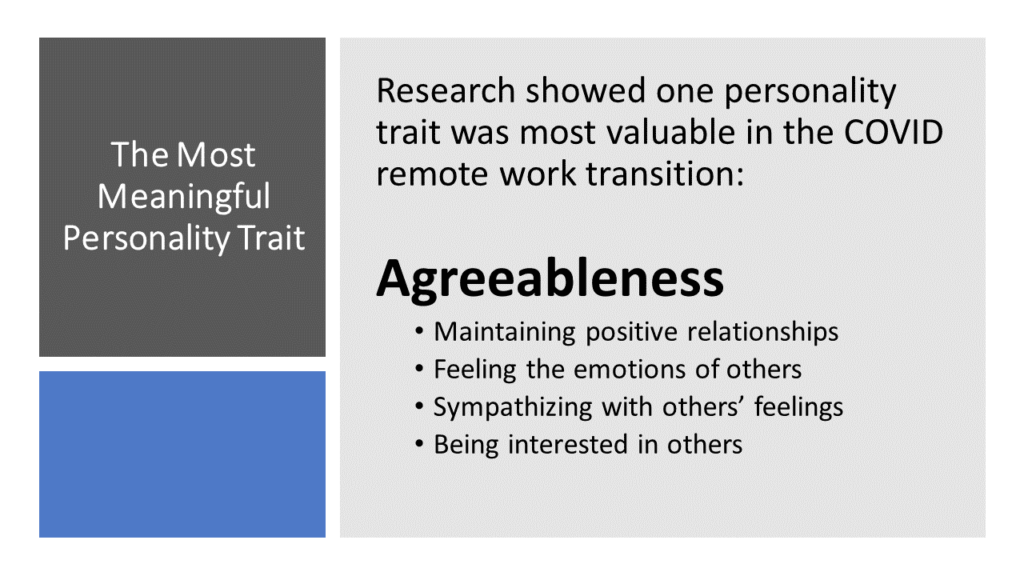

One study referenced in HBR showed that when employers moved to remote work, one character trait stood out as a tool to help people transition successfully to a more virtual environment. It wasn’t their amount of technology savviness, their age, or even their tendency toward introversion. It was their level of agreeableness.

Digital Interaction is Taxing and Requires More Work, Not Less

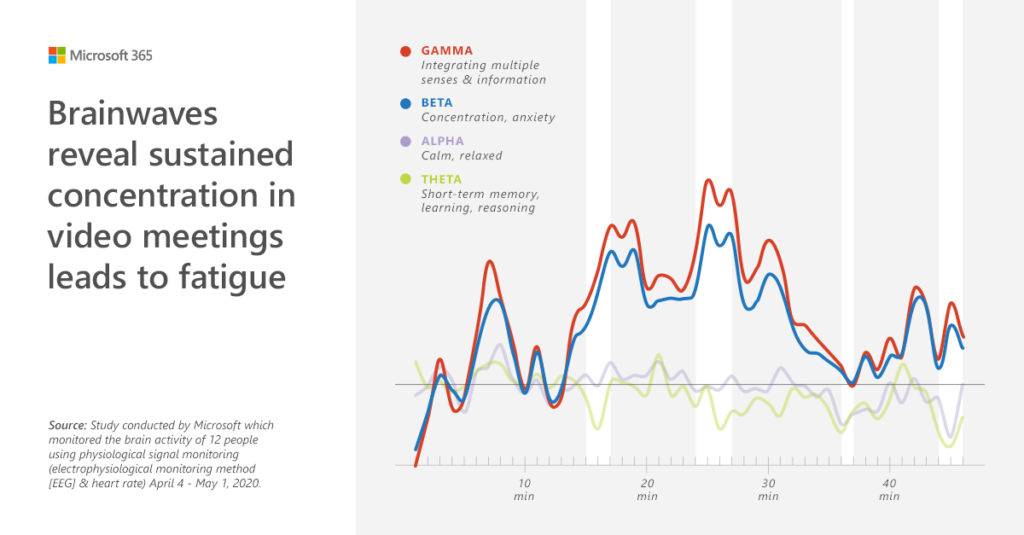

Data from Microsoft show that digital interactions require more intense brain activity to stay engaged. “Zoom Fatigue” has been the source of countless memes and jokes, but the scientific evidence shows that it’s a very real phenomenon. Because of a lack of visual cues, having a conversation remotely, even with two-way video, is still more mentally challenging. Additionally, the data show that it’s harder to focus the longer the session goes, which is an argument for shorter, more targeted conversations.

“Zoom” has become synonymous with online meetings (even though Microsoft’s Teams product is now serving more than 75 million active daily users), and in some cases it has become a piece of the fabric of our own lives.

As our own family gears up for virtual school this fall, we’re thinking a lot about this one and how to get the most out of the time involved in virtual meetings. In the spring we saw almost everything you can imagine happening within the virtual meeting platform, from children’s extracurricular lessons to family game nights and more. It may be that we need to look more strategically at how to use these meetings for the “right” sessions and back off a bit from using them for every single interaction at work, especially if they are leading to fatigue that cascades as the day continues, limiting our effectiveness.

Neuroscience data show that we have a finite amount of willpower per day. If we spend it all focusing and engaging intently in a web conference, we will not have it to think creatively, solve problems, or brainstorm with colleagues. One of the things I’ve taken to as a personal practice is blocking off one meeting-free day per week. That day without meetings is not only more productive, but it’s productive in the actual deep, creative work that is impossible to do in a day crammed full of meetings.

What We Lose in Remote Work Environments

The fatigue factor isn’t the only cost to a remote environment. Dr. Ben Waber, a visiting scientist for MIT, has demonstrated through years of research on remote teams that taking an organization to a more virtual approach can be tricky. What we often assume is that we will lose the collaboration that we had by having people in the same physical space.

However, the evidence shows that we often make up for that by intentionally scheduling more videoconferencing calls and conversations. Sounds like a net neutral change at least, right?

Not exactly.

The issue is we miss out on that “casual innovation” that happens when Monique has a neat idea to share with Jill and they grab Tom to do a whiteboard session on the topic. That kind of casual or spontaneous innovation (that leads to very tangible results in many cases) doesn’t happen as often in a virtual environment. Let me put it in practical terms:

The implications of going remote long-term are lower innovation unless something is done intentionally to emphasize and enforce the need for it. This is a compounding problem over time, because losing one unit of innovation this year can set your firm back next year, and that lost revenue means less to invest in innovation the next year, and so on.

Death by a thousand cuts–innovation style.

So, what’s the solution?

During a recent episode of We’re Only Human I talked about a dozen ways to engage and interact with teams that are remote, and that includes those that are new to this concept as well as those more established remote teams. The truth is that science hasn’t yet pinpointed the exact way to solve this problem, and because there are many variables to consider, the approach will likely vary from company to company.

The answer then, is to leverage some of the core human skills of work that are outlined in my book Artificial Intelligence for HR:

- How can we think through new creative approaches to solve this issue?

- How can we leverage the natural curiosity of the workforce?

- How can we encourage better and more spontaneous collaboration?

- How can we show compassion to those in this challenging time?

The good news for now is that data from Georgetown University and INSEAD show that teams with an all remote workforce are better coordinated and have stronger team dynamics.

If an office has a critical mass of workers and the rest are remote in their own homes, those dynamics suffer because it creates multiple layers of collaboration physically that aren’t apparent remotely. For those that are staying remote either for the near-term or the longer term, this is a positive if workers are trying to succeed using remote work from the safety of their own homes. Translation: the bigger the concentration of your workforce that is remote, the easier it is for them to create collaborative environments together. If there’s a mixture of virtual and in-person, it’s harder to make that work.

The Role of Managers and Leaders

Data show that all of the work we do in the HR space–culture development, training, benefits, and more–account for just 30% of someone’s satisfaction on the job. The other 70% is entirely dependent on the person’s direct supervisor.

Data published in Harvard Business Review showed that in some populations, about half of workers were working ten-plus hour days after the lockdown began. This is due in part to a lack of clear communications from the company and from individual managers. Just as many workers have never had a chance to work remotely, many leaders have never had to manage an employee they could not see physically on the job each day. Managing a remote or virtual team requires a different approach.

While the things that make a good leader in person can translate to a remote environment (recognition for results, leveraging worker strengths, prioritizing development and growth), it requires more intentionality to make this work when you do not see the person that reports to you on a regular basis.

Data from Quantum Workplace from over 700,000 employee responses showed that while engagement initially dropped during the COVID crisis, it rose more quickly than expected afterward. The data is fascinating, but check out the factors that drove engagement higher:

- The largest year-over-year item-level differences were related to communication and leadership with seven and eight percent growth in favorability, respectively;

- Increased favorability in health, wellbeing, and work-life balance also drove increases in employee engagement; and,

- Favorability regarding compensation and benefits also grew by seven and five percent, respectively.

Factor number one? Leadership communication. There’s no substitute for leadership, and when it comes to a crisis, that is doubly true.

I thought it was fascinating to see that increased health, wellbeing, and work-life balance also appeared in the study, even though we see from other data sets that people are working more hours on average. The first time I had a job where I worked remotely, I remember realizing that I was saving up to three hours a day transitioning to and from work and that I could be more productive using some of that time while still feeling like I got the better end of the deal from an employment perspective. While anecdotal, that may factor into why we see people working more hours but still enjoying higher satisfaction with work-life balance.

In one talk with an executive at Boeing, the person explained that this is the first time in several years that they have been able to get their work done AND spend time with children, cook meals with the family, and get personal exercise without having to explicitly take time off work to do so. As people settle into the expectation of remote work this may change, but it’s been wonderful to see employers responding and adapting to serve their people however they can.

A Note on Deskless Workers

While much of this analysis has looked at white collar professions and office space, where flexibility is somewhat built-in, there are a significant number of workers that are not working in an office or more traditional setting–they are often referred to as “deskless” workers, and some estimates put this percentage as high as 80% of the overall global workforce. Mercer data show that 55% of employers agree that redesigning the physical workplace to increase employee safety is a top priority going forward.

Our study on the evolving employer communication technology landscape shows a range of new technologies that can help to stay connected with workers that don’t sit at a desk or visit an office on a regular basis. These workers, in some cases, are still working as normal, albeit with protective equipment and other safeguards in place. And they often do not have an email account or other standard method to receive communication from their employer.

Whether these workers are on a shop floor or a job site (construction, healthcare, education, retail, etc.), they still have a very real need for communication with their employer, and it’s even more critical with the fast-paced nature of work that is occurring right now.

These workers don’t have to worry about Zoom fatigue, but they do have a much higher risk of health issues from COVID. In our discussions with employers, we’ve heard a considerable number of stories about workers that are worried about health issues and cannot return to work without considerable changes to the environment to ensure personal health and safety.

BLR recently published findings from a study of deskless workers and found that these individuals were unhappy with their benefits, their flexibility, and their support from their employers both pre- and post-COVID. It would be intriguing to cross reference the data from the Quantum study mentioned above and look at it based on the types of workers (office vs deskless) to see what the differences might be and how we might address them holistically.

There is not an easy solution to this problem. One of the technology areas that has virtually exploded in the last month or two is around contact tracing, which promised to tell which employees spent time around others and for how long, which can be valuable if there is a positive COVID test in the workplace. Initially there were thoughts that tech giants Google and Apple might be able to solve this since they make the software for the majority of personal communication devices, but that hasn’t proved to be as fruitful as expected.

Relevant side note: I’ve been inundated with about requests to view contact tracing technology from new providers serving the HR audience over the last few weeks. I know that Workday and Oracle have worked to update their technology platforms to allow for better reporting and tracking of COVID issues with health and safety tools. It appears we have yet a new category for HR technology applications.

Parents and the Human Nature of Work

Our team participated in an informal focus group made up of several dozen HR leaders from all levels, industries, and company sizes to talk about adaptability in the current climate. One of the key themes that came out of the discussion was around working from home.

No, they didn’t want to talk about logistics, resources, or collaboration. They wanted to talk about children. Over 30 million US families have at least one child, and employees that are trying to work from home while external childcare is unavailable are finding it’s easier said than done. Full disclosure: we have four kids 10 and under in our home.

A silver lining of many people having to work from home is that most of us don’t blink when a kid pops up on a Zoom meeting or stops to ask for help during a conference call. However, that doesn’t make it easier in managing the day-to-day stress of trying to get work done and taking care of children.

In one study, researchers found that the only survey item ranking higher than fear of Coronavirus spread is the fear that children are missing out on development opportunities due to being at home.

Is this the only problem? No, but it could have lasting implications with a stop/start return to whatever normal looks like in the future. For what it’s worth, 60% of families want to return to their previous childcare arrangements while the others are considering a range of alternatives with smaller group sizes to limit exposure and risk.

Like many of the conversations during this broader discussion, there’s not a simple, easy answer to solving this challenge. What is has done, though, is highlighted the critical role that the educational and childcare sectors play in enabling workers to perform on the job. Prior to this, it may have been debatable. Now? We can clearly see that we can get more productivity, focus, and creativity from people when they aren’t worried about their children.

Putting It All Together

From a personal standpoint, a family friend just left a 20+ year military career to move into the private sector and was looking forward to the transition. The first day on the job he was assigned a laptop and sent home to work remotely for the foreseeable future. This is not the career he was envisioning.

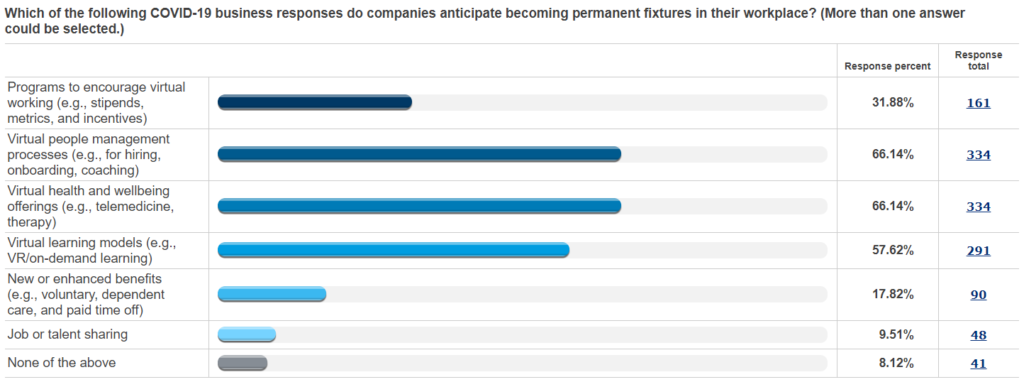

From a talent perspective, if this kind of thing becomes a new default for the workforce, we need to rethink many of the longstanding practices around recruiting, onboarding, learning, and everyday engagement. Mercer’s report shows that this move to more virtual people management will be a standard feature for HR teams going forward.

The research we’ve touched on here shows that we have some aspects figured out and some are still needing to be addressed when it comes to remote work, workforce engagement, and similar factors.

The workforce feels, at least at this point, like HR and the leadership teams are doing everything they can to support their needs. Is it perfect? No. But we are all in this together, and employees realize that and value what has been and continues to be done on their behalf.

Resources

- https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/blog/2020/07/08/future-work-good-challenging-unknown/

- https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20200629005100/en/

- https://www.cipd.co.uk/about/media/press/home-working-increases

- https://hbr.org/2020/07/the-implications-of-working-without-an-office

- https://app.keysurvey.com/reportmodule/REPORT4/report/41497603/41204105/5f7f8ac36ed9b505463e562c93410306?Dir=&Enc_Dir=8cb84448&av=IxnIBAm77ac%3D&afterVoting=d49f47d22482&msig=bf1679368151bd9395ae6e843c7a35c3

- https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/15/small-businesses-rehire-staff-but-cut-pay-and-hours-survey-finds.html

- https://www.pwc.com/us/en/library/covid-19/us-remote-work-survey.html

- https://www.xerox.com/en-us/about/future-of-work-pandemic-era

- https://www.ehstoday.com/covid19/article/21130371/50-of-us-employees-worry-about-workplace-exposure-to-covid19

- http://quantumworkplace.com/2020engagement

- https://kenaninstitute.unc.edu/kenan-insight/who-cares-assessing-the-impact-of-the-cares-act/

- https://www.gallup.com/workplace/313358/covid-continues-employees-feeling-less-prepared.aspx

- https://www.insurancejournal.com/news/national/2020/06/08/571298.htm

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/servicenow/2020/07/17/will-covid-19-ruin-remote-work-infographic/

Ben Eubanks is the Chief Research Officer at Lighthouse Research & Advisory. He is an author, speaker, and researcher with a passion for telling stories and making complex topics easy to understand.

His latest book Talent Scarcity answers the question every business leader has asked in recent years: “Where are all the people, and how do we get them back to work?” It shares practical and strategic recruiting and retention ideas and case studies for every employer.

His first book, Artificial Intelligence for HR, is the world’s most-cited resource on AI applications for hiring, development, and employee experience.

Ben has more than 10 years of experience both as an HR/recruiting executive as well as a researcher on workplace topics. His work is practical, relevant, and valued by practitioners from F100 firms to SMB organizations across the globe.

He has spoken to tens of thousands of HR professionals across the globe and enjoys sharing about technology, talent practices, and more. His speaking credits include the SHRM Annual Conference, Seminarium International, PeopleMatters Dubai and India, and over 100 other notable events.